Grantee spotlight:

Healing and transformation through movement

Exit12 Dance Company is a nonprofit organization co-founded in 2007 by Román Baca, a former U.S. Marine and ballet dancer. The company uses dance as a medium for expressing the experiences of veterans and promoting healing from the physical and emotional scars of war. The heart of Exit12’s program is an eight-week workshop designed specifically for veterans. It provides participants with space to communicate their feelings nonverbally, which can be particularly beneficial for those who find it difficult to talk about their experiences.

In 2022, Exit12 received an inaugural Creative Forces Community Engagement grant to support its workshop series. In 2023, this program culminated in a public performance on the Intrepid Museum in New York City, housed on the WWII aircraft carrier Intrepid. Participants showcased what they learned to a thrilled audience of friends, family, and supporters. The first-hand stories of the veterans shared here show how the arts can be a powerful tool for healing and transformation. Programs like this provide a space for expression and create a sense of belonging and empowerment for those who have served our country.

It feels like water flowing, like the wind, like love and care. When I’m dancing with others, it feels like a kind of embrace I’ve never had before.

Dãmasa Doyle, U.S. Navy veteran and Exit12 program participant

Truths Colliding: the making of a performance

Transcript

[Exit12 Dance Company was awarded an NEA Creative Forces Community Engagement grant. With it, they were able to create a workshop series for veterans and refugees to work through the hidden wounds of war. The result was a powerful performance of Truths Colliding at the Intrepid Museum in NYC. A male dancer holds a female dancer off the ground as he twirls. They both wear tight undergarments the same color as their white skin.]

Román Baca:

Dance has a way of transforming the way we embody military training.

[Dancers perform modern dance wearing military fatigues. A male dancer pushes a female dancer to the ground.]

[Caption: Román Baca, Exit12 Dance Company co-founder and artistic director, USMC veteran. Román is Hispanic and has short black hair. He's in his late forties.]

Román Baca:

Military members are much like dancers. They learn choreographed movement, they rehearse choreographed movement, and then they might have a couple of minutes or a couple of hours to actually perform their choreographed movement in the theater of war. Dance offers the opportunity to move people away from that harsh military training into a space where they can reconnect with love, with joy, with imagination, and with others again.

[Caption: Everett Cox, US Army veteran, artist. Everett, a white man with white hair in his seventies sits outside on a picnic table gazing across a green valley.]

Everett Cox:

I volunteered for Vietnam in 1969. 79 days and I had a breakdown.

[He writes in a notebook.]

When I came back, I traveled for months, hitchhiked all over the country. I was a mess and I didn't know how messy.

[Caption: Jenny Pacanowski, US Army veteran, artist. Jenny is a white woman in her forties.]

Jenny Pacanowski:

I was a medic on the front lines running medical support for convoys, which is like 911 on the road. My transition to the civilian world was very challenging.

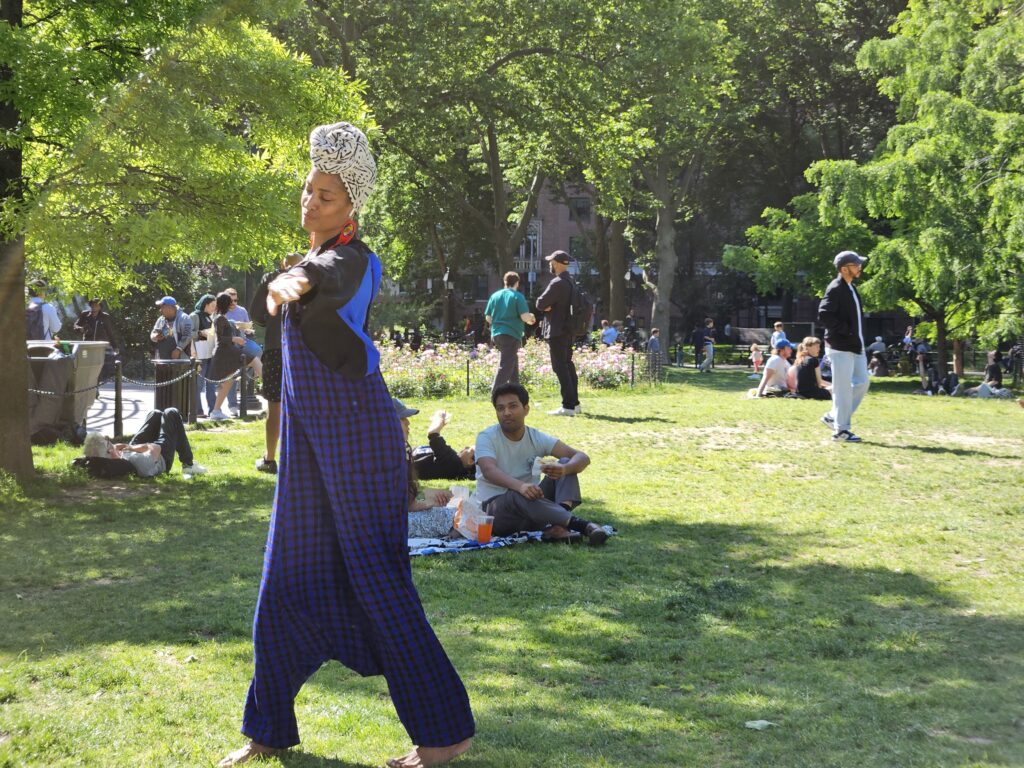

[A black woman in her forties who wears a hair wrap walks through a park with a younger man.]

Dãmasa Doyle:

I had grown up in some chaos. I was really searching at a young age for stability. Around 19, I joined the Navy to become a cryptologist.

[Caption: Dãmasa Doyle, US Navy veteran, artist.]

I was stationed in Japan where I spent three years.

[A white man with brown hair in his fifties writes in a notebook in a park.]

Anthony Roberts:

I'm a retired army officer after a 30-year career. It's been a very hard adjustment to be fully in the civilian world now.

[Caption: Anthony Roberts, US Army veteran, artist.]

In some ways you feel adrift.

[In a dance studio, Anthony Roberts holds out his hand along with other veterans in choreographed movement.]

Román Baca:

Exit12 Dance Company started working with military veterans and bringing them into the studio about 2011, and what we have developed is a workshop that brings them into a room.

[Jenny carries pages as she leads a group in a dance workshop.]

Introduces them to the concept of creativity and imagination, gets them moving in a very easy way.

[In the sunlit rehearsal space, a white man with a tattoo on his ear clenches his fists as a white woman with long blonde hair hugs her arms to her chest.]

And then scaffolds that experience so that as they move through, they're doing harder and harder tasks.

[The veterans stand apart from each other, moving separately.]

And they're sharing more important parts of themself.

[Six people place their hands on each other's shoulders and move forward and back as a group. Another group walks in a curved line, holding the shoulder of the person in front of them.]

Anthony Roberts:

What's interesting about the military and its movement, and I noticed this during my first rehearsal, is that the only choreography with which I was familiar, involves holding a weapon.

[In another studio, a man punches Román's open palms repeatedly. Then Román salutes his reflection in a wall of mirrors as he spins.]

Translating that into non-confrontational movement has been both liberating and also frightening.

Jenny Pacanowski:

I'm really used to being in my head, so moving into my body can be a really nice relief. I have my own kind of inner dialogue while in the workshop moving around, like, how can I let this go? How can I breathe this way?

Dãmasa Doyle:

It was really this exploration of how do I save my life and realizing that the trauma was activating me, and that I was feeling like I was in an ocean and I was drowning.

[Damãsa dances in a park.]

[Caption: Adrienne de La Fuente, Exit12 Dance Company, executive director and dancer. Adrienne is a white woman in her thirties.]

Adrienne:

One of the things I've definitely learned about trauma is the way that it narrows down the mind. Dance allows us to go big and to have an expression of really serious emotion that allows people to approximate something that was really difficult without having to go fully through it, and to create a safer version of that moment.

[Román addresses the veterans who stand in a large circle around him.]

Román Baca:

The next time you do your movement, think about the word that you have in your pocket, and I want to see if you can transform the movement you've just done to reflect the word in your pocket.

[A veteran's t-shirt reads 'Stories of War.']

If I was doing something frantic…

[Román waves his arms.]

And the word in my pocket was peaceful, I might just let this float a little bit, change the quality.

[He floats his arms as he drifts in a circle.]

Change the timing, maybe change the level the way you want it to feel, the way you want it to look, to reflect the emotion you have in your pocket.

[Outside, Anthony reads from his notebook to Jenny and she laughs. Anthony:]

Anthony Roberts:

How do I feel? Still very uncertain, very tense until I'm actually doing it and kind of get out of my head a little bit and just focus on the movement, instead of worrying about what it looks like and just purging myself of whatever I'm feeling through movement.

[In the studio, Anthony stands beside Román and they hold out their fists. Jenny:]

Jenny Pacanowski:

In those moments when I'm feeling true, full, authentic joy, I don't feel pain.

[Dãmasa sits in the park with a younger man and closes her eyes and nods her head.]

Dãmasa Doyle:

Chaos is feeling like at any moment, I am pushed into a space and time that was not my choosing.

[In studio, she punches her fist out in front of her, then waves her arms over her head.]

I realized that I had to find a way through and I had to find my joy to release myself from chaos and be in my purpose.

[Jenny and Anthony stroll on a dock past Navy vessels to the Intrepid Museum. In a carpeted room, veterans sit at folding tables talking and laughing.]

Román Baca:

By staying connected with Creative Forces, we started to build a community.

Adrienne:

We're bringing in those affected by conflict and giving them a space to move through that.

Román Baca:

When we thought about Truths Colliding and bringing veterans together to create a work, we thought about bringing other people impacted by war into the space, like refugees from the war in Ukraine.

[Female twins in their thirties with long strawberry blonde hair sit in the studio.]

To create understanding, to create dialogue that could help the conversations about Iraq, Afghanistan and Ukraine not disappear.

[Román stands in a circle with the veterans and they all hold hands and bow their heads.]

We know that the minute we step out of the room onto the stage, the fun happens. And there's no right out there and there is no wrong, it is just live. And give your hearts to the audience because I've seen them and they are beautiful. Have a wonderful, wonderful show.

[An audience arrives and sits on folding chairs in a warehouse space. They read the programs. The veterans perform in front of a gray curtain. They move separately, then come together as a group and hold their hands above their heads.]

Dãmasa Doyle:

Without community, we are lost. Without movement and expression, we're in trouble, and it keeps us in our joy. It also helps us transmute grief.

[Several veterans thrust out their chests then rush forward. They hold their hands above their heads in unison, then shake their hands towards the audience. Anthony:]

Anthony Roberts:

The more intense the experiences that you're working through, the more necessary the need to express them becomes. Sometimes it's a poem, it's a novel, it's a piece of music. It's a dance.

Everett Cox:

One of the most valuable things I lost in Vietnam was a sense of camaraderie. The military is built around camaraderie.

[Everett holds Dãmasa's arm during the performance.]

We have to support each other, we have to keep each other safe, and I felt that shattered in Vietnam. Working with Exit12 is to recreate camaraderie. It's powerful to link arms and dance together.

[The dancers join hands and touch shoulders as they flock in a circle. Román:]

Román Baca:

In Truths Colliding, we're getting a bunch of service members who served to stand up and say, "We were impacted by war. We are impacted by service, and we have trauma." And hopefully they can be an example to those who struggle, and maybe a motivation to talk about it, to reach out for support, or to get help.

[Román Baca stands with the veterans and applauds, then he steps forward and with his hands on his heart, he smiles as he bows. He gestures to the veterans.]

[The audience gets to their feet as the veterans in the dance company link hands and bow.]

[Title: National Endowment for the Arts, Creative Forces. Creative Forces. NEA Military Healing Arts Network is an initiative of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with the U.S Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs that seeks to improve the health, well-being and quality of life for military and veteran populations exposed to trauma, as well as their families and caregivers.]

Find our full Accessibility Statement in the footer.

Participant Spotlight:

Anthony Roberts

Anthony Roberts is a retired U.S. Army officer with a 30-year career behind him. From Baltimore’s rough neighborhoods, he joined the military to escape a youth marred by tragedy. His career in the Army, marked by experiences from Fort Benning to Afghanistan, shaped him profoundly. A graduate of The New School in New York City with a Masters of Fine Arts, his poetry has been published in Southerly Literary Journal, The Other Voices Poetry Anthology, and Vox Poetica, among others. He has also published two books: Pigtown and The Clearing Barrel.

Dãmasa Doyle

Dãmasa Doyle is a U.S. Navy veteran, born and raised in Chicago with five sisters and three brothers in a close-knit family. She left Chicago at 19 and joined the Navy, just as her Vietnam veteran father had done. Going directly from basic training to Japan, she trained as a Cryptologist and was stationed there for three years, coming to love the routines, the order, and everything about Japanese culture. From there, she went into high fashion modeling for 15 years, then the hospitality industry. She now works in the wellness field.

We are each finding our own ways through, and that’s beautiful, but we can’t do any of this alone. We can’t always heal, even when we think we can. We need community, people standing beside us who understand; we need people to catch us before we fall. Being together in movement, in words, motion, song, dance, and ritual gets us to support our own and each other’s journeys into civilian life. We reach out to those who may feel like they are drowning, and together, we can rise.

Dãmasa Doyle, U.S. Navy veteran and Exit12 program participant

Healing through creative expression

Dance is a powerful form of expression and can be a tool for people dealing with trauma.

For Dãmasa, the arts have been a lifelong companion, aiding her in navigating the complexities of life. Her involvement with Exit12 has deepened this connection, allowing her to find solace and strength in her creative pursuits. The act of storytelling, whether through dance, writing, or music, serves as a bridge connecting her to her ancestors and a sense of communal history. This narrative underscores the essential role of creative expression in not only coping with personal traumas but also in fostering a deep sense of belonging and understanding within a community.

Dãmasa shared that “the writing prompt exercises we did with Exit12 came easily for me. It took a lot of courage to record our writing and to listen to my voice telling my story. As a Black woman, it’s not always possible to have the opportunity to share my story, but I feel safe speaking and dancing within this group that feels like family. ”

Despite no prior experience in dance and some initial reservations, Anthony found that movement allowed him to process emotions differently than words. He describes his initial experience with dance as tense and blocked, yet gradually, it became a channel for self-expression and healing. The transformation wasn’t just physical; it was deeply psychological and emotional.

How does dance feel? I feel like I look like Joe Cocker after happy hour…but that’s okay. I’m still very uncertain, very tense until I’m actually doing it. I’ve definitely felt a sense of release, peace, coming to terms with what happened through the movement.

Anthony Roberts, U.S. Army veteran and Exit12 program participant

From service to civilian life

The transition from military service to civilian life often presents unique challenges, including symptoms of post-traumatic stress, re-integration into civilian society, and finding new means of self-expression and identity. In providing a structured creative outlet for emotional expression, Exit12 creates community to combat isolation. The routine and rigor of a multi-week course can provide familiar structure, aiding in the adjustment to a less regimented civilian lifestyle.

“It’s been a very hard adjustment…you feel adrift,” Anthony shared about his transition to civilian life. “I’m no longer ‘Major Roberts,’ I’m no longer ‘Sir.’ I have to dress myself in regular clothes every day. Even in my new career — I realize that interactions are different, even language is different.”

Fostering joyful connection

Dãmasa and Anthony’s experiences with Exit12 underscore the essential role of art in fostering community and understanding. The shared language of movement creates a vital bond among veterans, offering a sanctuary where words are unnecessary. This sense of unspoken understanding and mutual respect is a powerful antidote to isolation, highlighting the importance of community in the healing process. Their stories are just two experiences from the program that illustrate how art can be a conduit for joy, connection, and profound personal transformation.

It’s been in some ways like a homecoming, being with people who just ‘get it.’ There is a deep underlying emotion and feeling of connection. We’re all working through something, whether it’s someone whose war ended before I was born, who’s still dealing with some of the things that took place there. Or somebody who may not necessarily be dealing with combat-related trauma, but trauma associated with their service. Knowing that really adds a degree of solemnity to what we do, even beneath the veneer or the shared humor.

Anthony Roberts, U.S. Army veteran and Exit12 program participant